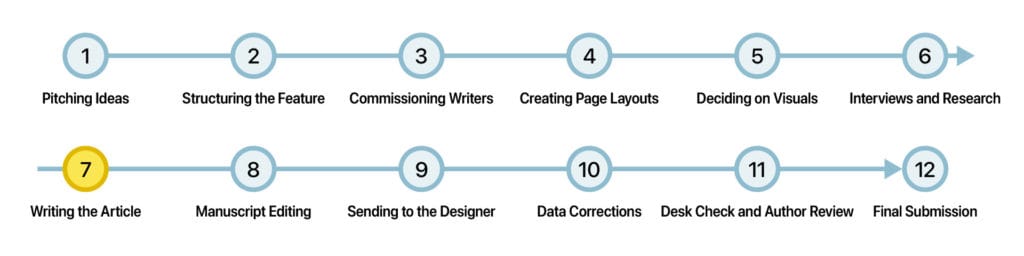

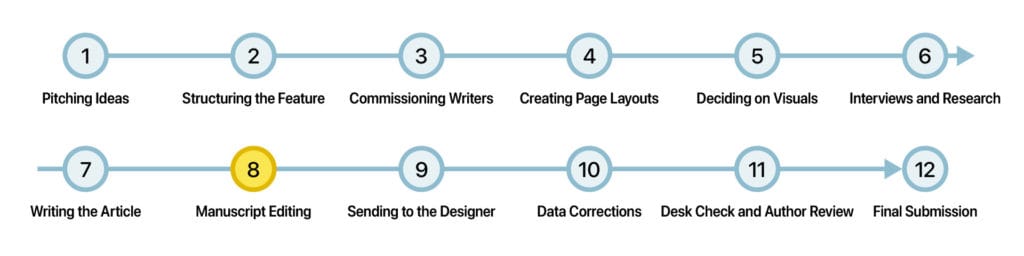

In Part 1, I discussed the process from pitching ideas to conducting interviews. In Part 2, I’ll walk you through how we transform manuscripts into finished articles ready for publication. This includes writing, manuscript editing, working with designers, proofreading, and final submission. These tasks may seem unglamorous, but this is where the editor’s true work comes to life.

Note: What I’m describing here is the workflow of “a particular publication” I’ve worked with. Editorial processes vary dramatically between publications. Please don’t generalize this as “how magazine editing works”—consider it just one example among many.

If you haven’t already, please check out Part 1 as well.

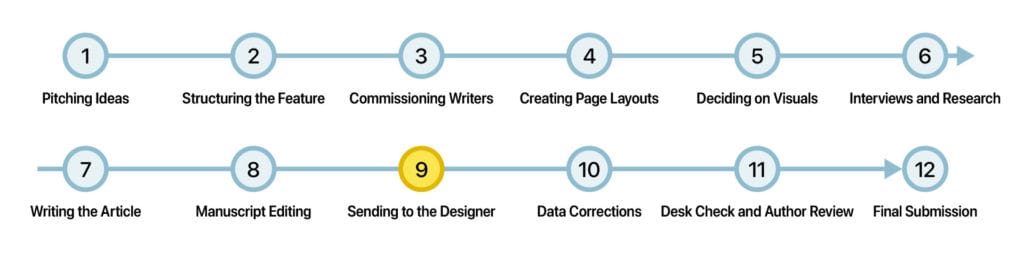

- 7. Writing the Article: To Write or to Delegate

- 8. Manuscript Editing: Preparing Copy for Publication

- 9. Sending Materials to the Designer: Passing the Baton

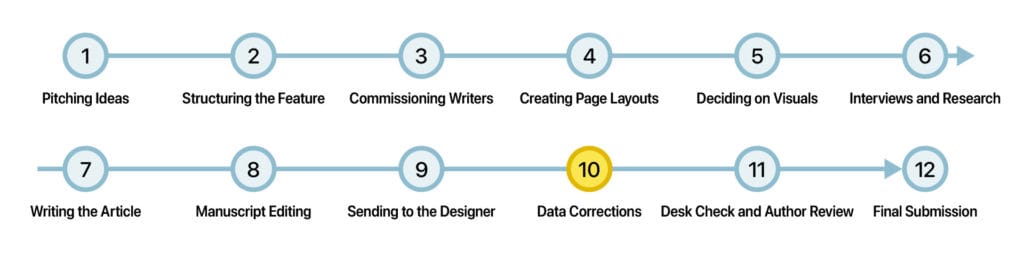

- 10. Receiving and Refining the First Proof: Polishing the Design

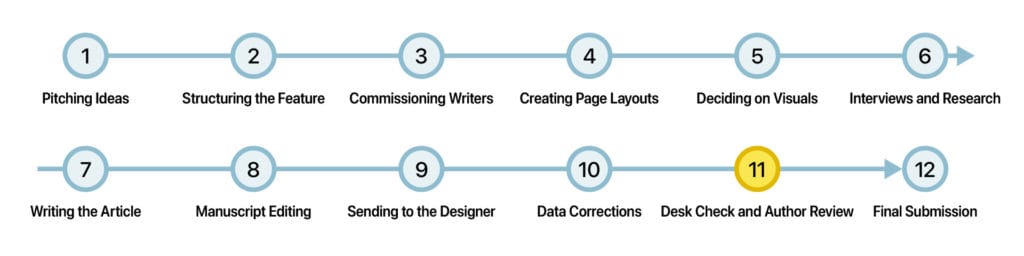

- 11. Desk Review and Author Proofing: Layers Upon Layers of Checks

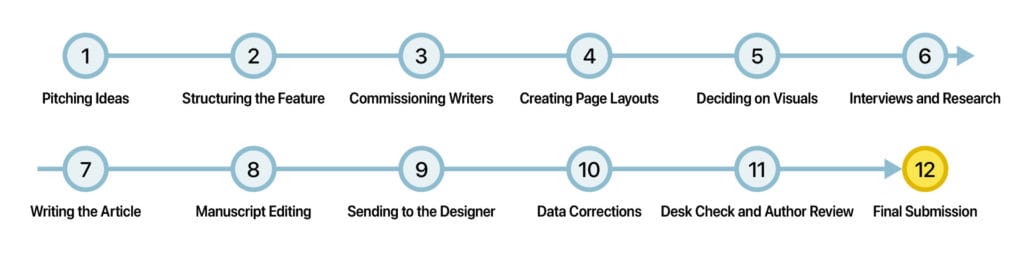

- 12. Final Submission: The “Good Work, Everyone” Moment

- Closing Thoughts

7. Writing the Article: To Write or to Delegate

For feature articles, I often handle both editing and writing myself. Typically, I write about half or a third of a feature’s total content rather than the entire thing.

Why do I choose to write myself rather than focusing solely on editing? There are three main reasons.

First, I simply want to write. The more I research a feature topic, the more fascinated I become. Once that curiosity kicks in, I naturally want to put it into words myself. Sometimes I start with a burning desire to write about a particular theme from the very beginning.

Second, there’s the matter of time efficiency. As I’ll discuss later, reviewing and editing a writer’s manuscript takes considerable time. In some cases, writing it myself from the start actually reduces the overall workload. This is especially true for articles that don’t require a distinctive authorial voice, or pieces composed of many short, factual segments.

Third—and this is the practical reality—I want to secure my own income. Related to the second point, manuscript editing takes significant time, and honestly, editing alone isn’t very lucrative. Writing the article myself means I can bill for both “writing fees” and “editing fees.”

That said, there are also cases where delegating to a freelance writer is the better choice. Again, three main reasons.

First, quality. For certain topics, there are writers better suited than me. If bringing in another writer will elevate the feature’s quality, I’ll absolutely make that call.

Second, avoiding tunnel vision. When one person handles both writing and editing, the article can become self-indulgent and one-sided. While that “bias” can sometimes add a personal touch, it can also alienate readers.

Third, schedule management. Taking on too much myself can derail timelines. Work almost always takes longer than expected—no matter how many years you’ve been doing this, scheduling remains challenging. When deciding how much to write myself, I’m careful not to exceed my capacity.

I’ll skip discussing writing techniques in this article. Perhaps I’ll cover that another time.<br>

8. Manuscript Editing: Preparing Copy for Publication

Once a writer submits their manuscript, I begin the process known as genkō seiri (原稿整理)—literally “manuscript arrangement.”

Note for international readers: Genkō seiri is a Japanese editorial term that encompasses what might be called “copy editing” or “manuscript preparation” in English-speaking publishing. However, it often involves a broader scope of work than typical copy editing, including fact-checking, rewriting for clarity, and preparing materials for the design phase.

This process involves making the submitted manuscript ready for publication while ensuring it’s in a format that facilitates the layout process. The scope of this work is extensive.

First: Does the content match what was commissioned? Are there any factual errors or ambiguities? Is the writing readable? Are there typos or misspellings? Does the style conform to the publication’s guidelines? Is the word count as specified?

After these checks, I request revisions or additions from the writer if needed. For issues I can reasonably fix myself, I make the changes directly.

During my early days as an editor, the mantra drilled into me was “the manuscript is always reader-first.” While that sounds noble, prioritizing “readability for the reader” sometimes meant stripping away a writer’s distinctive voice. As a junior editor, my work would come back from desk review covered in red marks (correction notes)—sometimes to the point where the original manuscript was unrecognizable.

That experience left me with a habit of heavily revising writers’ manuscripts.

Ideally, significant changes should be communicated to the writer with a request for a rewrite. But time constraints often meant I’d make the changes myself. Writers must have felt frustrated seeing their work transformed into something they didn’t intend. Looking back, I have many regrets about not communicating more thoughtfully.

By the way, “manuscript” here doesn’t just mean text—it includes zuban (図版), meaning images and photographs. At the publication I worked for, writers were generally responsible for providing visuals too. This was mostly screenshots, though sometimes hardware photography was required.

Preparing these images for the design phase is also the editor’s job. This includes converting color spaces from RGB to CMYK, changing file formats, applying mosaic effects to protect personal information, and performing image corrections on photographs.

9. Sending Materials to the Designer: Passing the Baton

Once the manuscript is ready, I send it to the designer. For substantial content like features, I send pages incrementally as they’re completed.

At this stage, I also revisit the rough layout (rafu—a sketch of the page design). The rough I created when commissioning the writer often differs from the final manuscript. For example, I might have planned for three images, but the actual article requires five. New layout ideas also emerge during the editing process, so I incorporate them as they come.

Any instructions for the designer get written directly into the rough or the text manuscript.

When sending materials, I clearly communicate the schedule: when I’ll deliver the remaining pages, when I need the first proof. Even with regular publications where the rhythm is established, explicit communication remains essential. Communication really is everything.

Of course, schedules slip sometimes. When that happens, I apologize properly. Well, I’m always apologizing, honestly…

10. Receiving and Refining the First Proof: Polishing the Design

When the designer delivers the first proof (shokō—the initial designed layout), I start by reviewing the overall design without focusing on the fine text details yet. Is the design aligned with my intentions? Is anything unclear or confusing? These are my primary concerns at this stage.

I also request a design review from the editor-in-chief. Once their feedback arrives, I compile it with my own notes and send revision requests to the designer.

What I always tried to do was communicate the “why”—the reasoning behind each requested change. Designers aren’t just executors; they’re partners in creating something together. …That said, I’ll admit my younger self wasn’t always mindful of this.

After design revisions are complete, I pull the data files. In the workflow I’m describing, we don’t ask the designer to make text corrections. Text edits are handled by the editor after receiving the files.

For text corrections, rather than fixing things sequentially from the first page, I tackle the big items first: standardizing headline lengths, fixing inconsistent formatting throughout the article. Then I move to the detailed text. Image cropping adjustments are also handled by the editor.

Editors at this publication were expected to be proficient in InDesign (Adobe’s page layout software). Having come from the printing industry, I already had layout software knowledge. But I imagine it’s tough for those who entered editing without that background.

The refinement process is a battle between the desire to do more and the constraints of time. I’d keep making revisions thinking “I want to make this more interesting” or “I want to make this clearer.”

Note for international readers: Computer magazines in Japan typically include extensive visual annotations—boxes, arrows, and callouts highlighting key areas within screenshots and diagrams. This practice is more elaborate than in many Western publications and is considered essential for reader comprehension.

Computer magazines frequently use boxes and arrows on images, and I paid careful attention to making these as clear as possible. Without highlighting where readers should focus, people tend to skip over visuals entirely. If an image gets skipped, that portion “dies.” So I mark attention points to ensure they catch the eye, whether readers want to look or not.

After completing these revisions, it’s time for desk review.

11. Desk Review and Author Proofing: Layers Upon Layers of Checks

“Desk review” (desuku chekku) refers to an article review by a desk-level editor.

Note for international readers: In Japanese magazine publishing, “desk” (desuku) refers to senior editorial positions—roughly equivalent to section editors, deputy editors, or managing editors in Western publications. The term comes from the traditional layout of newsrooms where senior editors sat at specific desks overseeing sections. A “desk check” is a quality review by these senior editors.

Desk-level editors include the editor-in-chief, deputy editor-in-chief, and section desk editors. If I’m at desk level myself, another desk editor or the editor-in-chief reviews my work.

The article comes back from desk review marked with corrections (akaji—literally “red characters,” meaning editorial markup), which I then address.

Simultaneously, I send a PDF to the writer for author proofing. For interview-based articles, I also send confirmation PDFs to the interviewees.

In practice, I contact them shortly before sending: “I plan to send this on 2026/03/11,” so they can set aside time. Sending a PDF out of the blue with “please review by tomorrow” would be inconsiderate.

In my younger days, I was terrible at scheduling these confirmations and caused trouble for many people. I have a lot of regretful memories.

The ideal workflow is to incorporate desk review corrections before sending materials for author proofing and source confirmation. But time constraints usually meant running desk review and author proofing in parallel. Even now, I rarely have the luxury of following the ideal sequence.

When author proofing or source confirmation yields corrections, I update the data. These revisions are, of course, also handled by the editor.

12. Final Submission: The “Good Work, Everyone” Moment

Once text corrections are complete, I return the data to the designer for a design review—checking whether my edits have broken anything in the layout and requesting any design-related fixes.

After the designer’s review comes the art director’s check. The art director is essentially the chief of the publication’s design department, providing final approval on visual elements.

Once the art director signs off, I pull the data one last time.

A final check. Reviewing until I’m satisfied, until I’m certain there are no errors. When I can finally say “this is truly the final version,” it’s time for nyūkō—submission to the printer.

Note for international readers: Nyūkō (入稿) literally means “submitting the manuscript” and refers to the final handoff of print-ready files to the printing company. In Japanese publishing, this moment is often celebrated as a significant milestone—the culmination of weeks of intensive work. Unlike Western workflows where “going to press” might be handled entirely by production staff, Japanese editors often remain deeply involved until this final moment.

(Note: In this publication’s workflow, there is no separate “copyediting” or “proofreading department” check stage.)

In the old days, I would load the data onto an MO disk, prepare printouts, and hand-deliver them to the printer. The office had a mailbox-like drop point for printer deliveries. Now everything is transmitted via server.

Note for international readers: MO (magneto-optical) disks were popular in Japanese publishing and design industries through the early 2000s, well after they had fallen out of use elsewhere. They offered reliable rewritable storage at a time when other options were limited.

Since becoming a freelance editor, I’ve delegated final submission to in-house editorial staff. I hand off the final data, and sometime later I receive the message: “Submitted.” That’s when the editing work for that issue finally concludes.

Occasionally, the team member handling submission catches typos I missed. I’m grateful for these multiple layers of checking. Though I’ve reviewed everything multiple times myself… how do errors still slip through?

After submission, I’m largely done, but the in-house editorial staff still has work: posting announcements on the website and social media, among other tasks. It’s all demanding work. Truly, お疲れ様でした—good work, everyone.

Note for international readers: Otsukaresama deshita (お疲れ様でした) is a Japanese phrase used to acknowledge someone’s hard work and effort. It’s commonly said at the end of a work day or project completion and has no direct English equivalent—combining elements of “good work,” “thank you for your efforts,” and “you must be tired.”

Closing Thoughts

This has been an overview of the magazine editing workflow I’ve practiced.

As I’ve repeated throughout: this is just “my story.” Editorial processes differ entirely between publications, and even within the same publication, different editors may work differently. If something here strikes you as wrong, it may well be something only I did.

Looking back, magazine editing really is quite demanding. But the challenges make it rewarding, and ultimately, it’s enjoyable work.

Print magazines will likely continue to decline. Even so, I still want to create print media.

If you have a publication that could use my help, please reach out. I can handle everything described in this article, and I’m flexible enough to adapt to different workflows.<br>

I hope to find some good opportunities…